By Deborah Kidd

Today’s research is capturing a multi-dimensional perspective of the globe that is rapidly refining conservation. Our view of the planet has never been more expansive, nor refined. Species are adapting to changing conditions, while technology is evolving what we can see, analyze, and understand, giving us the best chance yet to make a major impact for the health of our planet and every species that shares it.

Distinguished ecologists and scientists from Smithsonian Institution, Audubon, The Nature Conservancy, Esri, the E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation, and more, will convene in Washington, D.C. to share the latest knowledge and technology needed as we take on the challenge of the biodiversity extinction threat. The Smithsonian Institution and the E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation will welcome speakers from diverse sectors and perspectives to discuss how we can restore and protect biodiversity worldwide. We invite you to join the discussion at “Our Shared Future – Conversations in celebration of Half-Earth Day 2022.” The public event will be held October 13 at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C in the Baird Auditorium, from 12 pm to 5:30 pm. These vital conversations will go global as we share them online to mark Half-Earth Day 2022 on October 22.

Securing the biodiversity of species across our planet is not only important for planetary health, it is a vital ecosystem service for people, too, explained Dr. Dawn Wright, Chief Scientist at Esri and a featured speaker at the upcoming event.

“We’re talking about basic livelihood: Enough food to eat, fresh water and clean air,” she said. “Biodiversity is a goal where we can all find common ground.” Wright leads teams at Esri working to visualize a global view of biodiversity for many leading conservation organizations, including the Half-Earth Project, a program of the E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation. This connection of ecosystems and organisms across a worldwide network is only possible because of collaborations across federal, private, non-profit, academic, local and global institutions. A cross-sector and inclusive approach reflects the expansive efforts in partnership and science that are essential to protect global biodiversity.

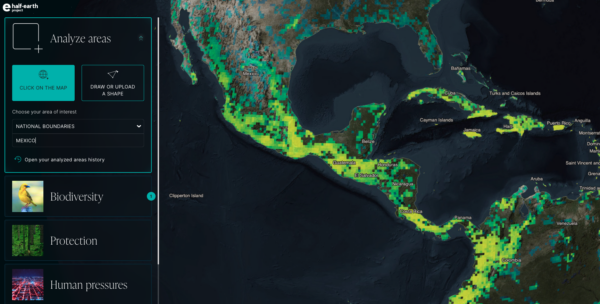

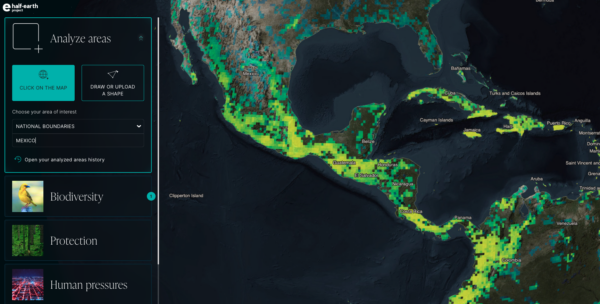

The Half-Earth Project Map is an example of these collaborations, and the October 13th event will provide a forum to showcase its role as an evidence-based research guide to support a biodiversity strategy that leaves no species behind. Thousands of data points create the most comprehensive picture yet of our planet’s landscapes and species—where they are changing, thriving, and degrading. The map is funded by the E. O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation and managed and developed by the Foundation and its partners at Yale University’s Center for Biodiversity and Global Change, Vizzuality, and Esri.

Wilsonosaura lizard, named after E.O. Wilson. photo: EdgarLehr

“In the last few years, we’ve been able to make huge leaps in our ability to predict where species occur across the globe and at an increasingly finer resolution,” said Alex Killion, the Yale center’s managing director. Across the world, scientists analyze images captured by NASA satellites recording the “constant pulse of the Earth.” Computer scientists aggregate data from this global network, Killion explained, “to highlight areas of concern, where habitat degradation is happening at a faster pace.”

Several of these priority areas are highlighted on the Half-Earth Project Map, like forests in Poland where the European Bison roams among the world’s largest oak trees or pine woodlands in Mexico where millions of monarch butterflies migrate for winter. Rotate toward Central Asia and the Alti Mountains, and a priority region spotlights the descendants of ice-age fauna like reindeer and steppe lemming.

Half-Earth Project Map, Mexico, 2022.

Visualizing these scientific advances in understanding the health and habitats of species not only makes biodiversity tangible for local communities, it is also an essential guide for policymakers at global, national, and local levels, shares Killion. Recent updates to the map incorporate finer resolution and new biodiversity layers, and new data and analyses consistently add to the collection.

The Half-Earth Project Map offers data visualization and biodiversity layers for global oceans, as well. But while satellite imagery is a powerful tool for land-based conservation, the technology is still limited for mapping ocean ecosystems and species. “Satellites that can see tree canopies or access land cover are blind in the ocean,” Esri’s Chief Scientist noted. Data collection on the open ocean is much more active, as scientists have to be within or directly on top of the environment they are studying. Wright is encouraged by technological advances in ocean mapping, with sensor-equipped buoys that record plants, animals, and local conditions, “giving us a better idea of the changing physical parameters that marine species depend on, including temperature, oxygen, and primary nutrients.”

Wright recently tested advanced side-scan sonar in the “Challenger Deep” site of the Pacific Ocean’s Mariana Trench. It was the first time this geospatial mapping technology had been applied at such depth, a technological feat that promises to accelerate our understanding of global oceans. The mission made history in more ways than one. Wright became the first person of African descent (of any gender) and the fifth woman to dive to the farthest depths of the ocean.

To learn more about Wright’s historic expedition to Challenger Deep, visit mappingthedeep-story.hub.arcgis.com.

Such inspiring milestones remind us that we are part of a global community, and that we must share the resources that sustain us. Later this year, the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity will establish a set of global targets toward reaching biodiversity goals. These targets will represent commitments by more than 150 nations to restore and protect biodiversity. Closer to home, policymakers in the United States are setting strategies to implement the 2021 America the Beautiful Initiative, which aims to restore, connect, and conserve 30 percent of US lands and waters by 2030.

Killion noted the scientific foundation that the Half-Earth Project Map has the potential to inform federal decisions, while also emphasizing its benefits for management at a local scale. “We have a large aggregation of information to inform national policy, but we are also able to make predictions at a level of specificity that a local conservationist can act on,” he said. “Policy is a high-level goal to guide us, but it comes down to people sitting around a map and deciding “are we going to restore this piece of land or that one?”

“A map is a common language” that cuts across borders and differences, Wright said. A geographic approach to biodiversity not only provides a comprehensive view of lands and waters, but can incorporate diverse perspectives of the people who live alongside them. “The essence of geography is pulling in different ways of knowing,” Wright said. “A geographic approach to conservation organizes and optimizes knowledge from all places.”

In the United States and North America, diverse voices and contributions are growing due to the increased inclusion of local knowledge and indigenous wisdom in policy and strategy. This overlooked perspective offers essential observations about species and landscapes, from ancestral perspectives through current cultural practices.

The discussions at “Our Shared Future”, a celebration of Half-Earth Day, aim to build on this multi-generational perspective, with speakers to include Queen Quet, Chieftess of the Gullah/Geechee Nation. Her leadership is helping to protect the salt marshes that the Gullah/Geechee consider part of their family—and that can serve as an important buffer to sea level rise. “Without being able to nourish our souls and our bodies via the waterways and estuaries that are our salt marsh areas,” Queen Quet explained, “Gullah/Geechee people wouldn’t thrive and our culture wouldn’t survive. So the life of the salt marsh is inextricably tied to our cultural continuation.”

Half-Earth Day celebrations like “Our Shared Future” offer a unique opportunity to connect technology with culture, and new insights with traditional knowledge. Don’t miss your chance to be part of these crucial conversations. Register to attend Our Shared Future here; and/or mark your calendar for the global release of the day’s panel’s on October 22, Half-Earth Day.