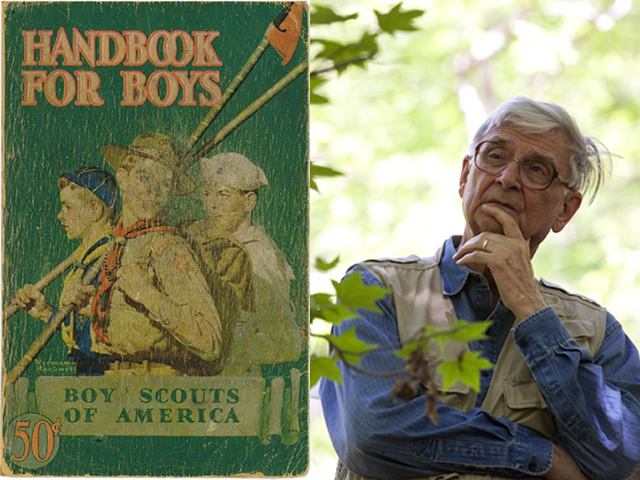

Writing in the New York Times, E.O. Wilson reflects on his childhood and the great influence that the 1942 edition of Handbook for Boys, the official guide of the Boy Scouts of America, has had on his life. Many of the themes E.O. Wilson touches on in this essay are essential components of the E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation’s educational initiatives, which have three key themes:

1. Awareness and Action: Using innovative techniques that generate broad public awareness around the importance of the living world.

2. Understanding and Inspiration: Developing compelling textbooks and curriculum that increase understanding and inspire caring stewardship.

3. Experience and Engagement: Nurturing our human connection with nature and the powerful way it can compel us to care about and protect the living world.

Read the full text of E.O. Wilson essay, “A Manual for Life,” below:

I read only two books cover to cover during high school. The first was Owen Wister’s The Virginian, which I found gathering dust in the parlor of the old Wilson house on Charleston Street in Mobile, Ala. Wister, along with issues of Collier’s, Life magazine, Reader’s Digest and the yellow-tinted Mobile Press-Register, made up the household literature. There was a public library a few blocks north of us on Government Street, but I never thought of going there. Libraries were not part of the culture in which I was raised.

My stepmother had grown up on a hardscrabble farm, and her ambitions for me were simply to finish school, get a job and clean up after myself. My father was a warmly affectionate man, when sober, but hampered intellectually; he dropped out of high school after freshman year. A traveling auditor in the Roosevelt-era Rural Electrification Administration, he moved us from town to town at an almost yearly pace. I attended 13 public schools in nine localities.

It wasn’t an optimal schedule for formal education. My grades were mediocre, and I can’t remember the name of a single teacher. Vanderbilt University understandably turned down my application for admission. I tried to enlist in the Army but was rejected because of blindness in one eye. Finally, the University of Alabama admitted me, and everything abruptly changed. The sun rose on my horizon. I flourished, and five years later, after earning bachelor’s and master’s degrees in biology, I was admitted to Harvard University as a Ph.D. student. Seven years later, at the age of 29, I was given a tenured professorship.

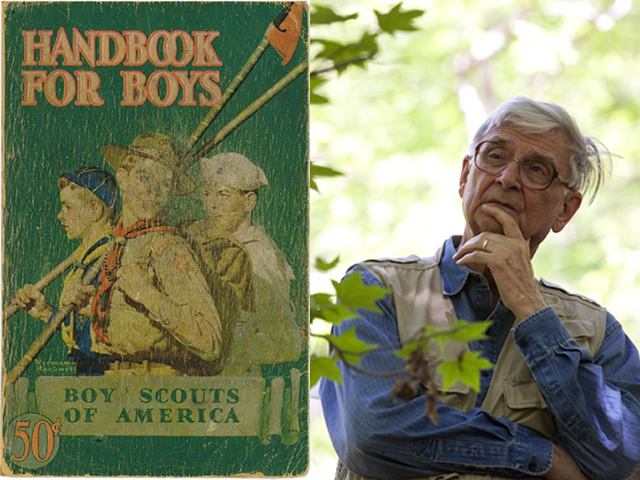

Coming to this metamorphosis brings me to the second book I read in high school, the book I devoured: the 1942 edition of Handbook for Boys, the official guide of the Boy Scouts of America. To this classic of literature (thus defined if literature is understood as writing that stirs the soul and a classic as a work that contributes to the growth of a civilization), I give credit for my secondary education.

The Handbook for Boys expresses the best of the American ethos as it was at the middle of the 20th century, unparalleled for its brilliance of pedagogy and its uncompromising declaration of democratic ideals. It espouses individualism, responsibility, empowerment and the philosophy of taking hold and learning by doing.

In its 680 pages are to be found the essentials of camping, field cooking, swimming, lifesaving, first aid, semaphore and Morse code, and seaworthy knot-tying; mapmaking, agriculture, patriotic and popular campsite songs; and, not least, elements of American history, including emphasis on the Constitution and Bill of Rights. In the midst of all this are incomplete but serviceable field guides to North American trees, birds, insects and mammals, and to the planets and constellations. The book is true to the maxim “Teach me, I forget; show me, I remember; involve me, I understand.”

Seven decades ago, it should be remembered, a much larger fraction of the American people lived on farms and in small towns. The Handbook was slanted to prepare young men principally for life in that world.

But it did more: It provided us with meaning and pleasure in the outdoors. It reinforced the conservation ethic, and celebrated American innovation in world culture.

Equally potent, the Handbook guided the boy upward in rank, Tenderfoot to Eagle, through tasks of increasing difficulty. The scout was expected to ascend at his own pace, by reading and consulting scoutmasters, parents and other mentors. This way he would have neither cause for embarrassment nor excuse for giving up. It was a technique I chose to use with my own students at Harvard.

The rewards of this purpose-driven approach were (and remain) the merit badges, certificates of accomplishment in particular fields of endeavor worn on the uniform’s sash. The authors of the “Handbook” were aware of the badges’ potential role in opening doors to future careers. In 1942, about 126 merit badges were included, from Aeronautics to Zoology. Combinations of badges were then listed as relevant for various occupations.

In my selection, I moved right past Artist, Doctor, Engineer and Merchant to Naturalist and Educator. And there I have stayed.

I haven’t watched the scout movement closely in many years, so I can’t judge how well it has adjusted to America’s shift to cities and suburbs. Gay youths are finally allowed to become scouts (although gay leaders are still excluded), reversing policies put in place by the anti-gay dogmas of the sponsoring churches. As I recall, sex of any kind was not rationally discussed in the Boy Scouts or, for that matter, anywhere else at the time; sex education ranged from abstemious to zero. The “Handbook” advised combating sexual urges with “hip baths”: sitting in water from 56 to 60 degrees Fahrenheit for 15 minutes at night before bed.

I’m well aware that to many, the Boy Scouts seem unsophisticated and outdated. But I ask doubters at least to consider this: If asked to decide who would be both successful in life and exceptionally useful to society, the graduating senior of an elite New England prep school or an Eagle Scout in Kansas, I’d vote for the Eagle Scout.

For more inspiring words from E.O. Wilson, please visit our Video Library.

Related: