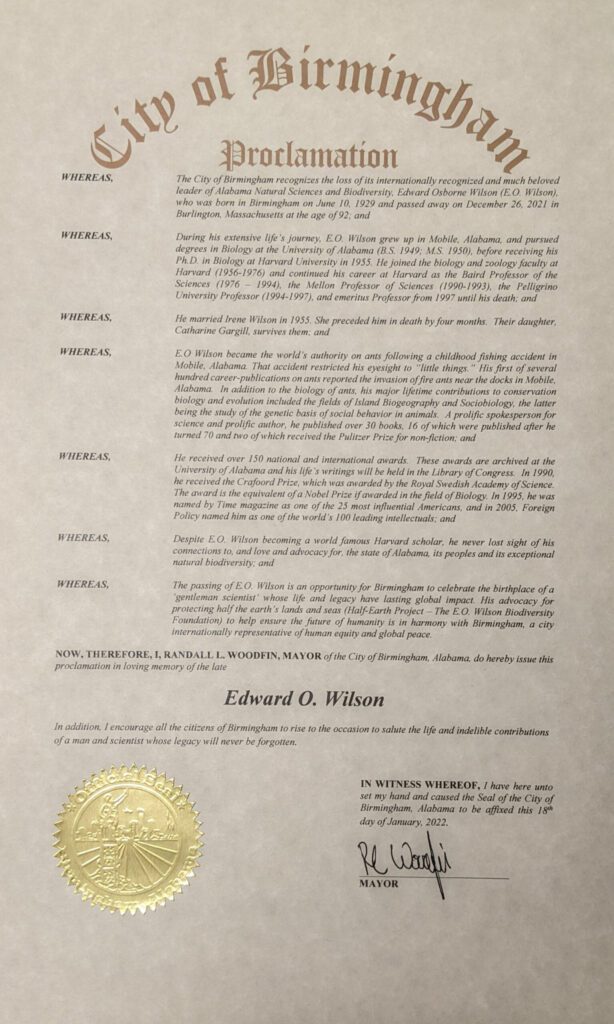

Birmingham Mayor Randall Woodin signed a Birmingham City Proclamation recognizing the passing of E.O. Wilson (1929 – 2021), his birth in the city of Birmingham, his remarkable contributions to Evolutionary Biology and Conservation Science and his lifelong dedication to the people and biodiversity of Alabama. Professor Wilson participated in several expeditions in Alabama led by Dr. Bill Finch, Executive Director of the Paint Rock Forest Research Center in recent years as captured by the 2015 PBS film, Ants and Men.

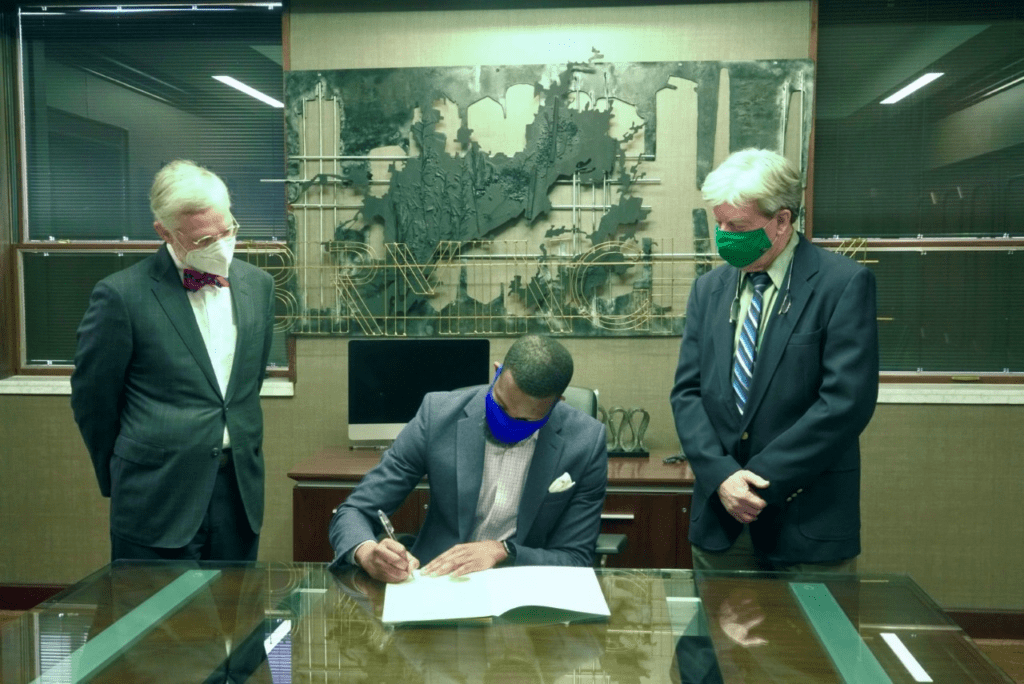

Dr. James McClintock (right) and Dr. Paul Erwing (left) share in the signing ceremony with Mayor Woodin.

Read the full proclamation from Birmingham City.

Professor Wilson’s passing was also recognized throughout the last month in state and local media.

FoxNews10 Mobile, Alabama (TV Report)

Renowned biologist and Alabama native E.O. Wilson dies at 92

Alabama.com

‘Famous in a way few Alabamians will ever be’: E.O. Wilson’s Alabama legacy recalled after his death

Archibald: Birmingham honors a Alabama giant

Crimson White (University of Alabama)

E.O. Wilson, UA alum and ‘father of sociobiology,’ dies at 9

University of Alabama News Center

UA Mourns Passing of Legend E.O. Wilson

TuscaloosaNews.com

Pioneering biologist E. O. Wilson had extensive Alabama ties

Dr. Bill Finch, Executive Director at the Paint Rock Forest Research Center and Principle Science Advisor, Half-Earth Project also wrote:

“When E.O. Wilson died this week, many here may not have recognized how he changed Alabama in the eyes of the world.

Those impressed by celebrity will be interested to know that Ed Wilson was likely the most famous Alabamian of his generation. There are plenty of people worldwide – in Europe, in South America, in China or Africa or much of North America — who would scratch their heads if you mentioned a football coach, but they’d know immediately that E.O. Wilson was among the most widely recognized and influential scientists of the 20th century.

Ed was famous because – in his research, in his many books and TV appearances — he gave the world a new way of thinking and talking about life. Ed made his entrance as the “ant man” – the world’s preeminent authority on ants. But the discovery and celebration of what Ed called “biodiversity” was central to his work. Nature for Ed wasn’t just beautiful scenery, or some philosophical ideal. Nature was first and foremost its components, its species, each and every one.

Just as Ed gave people new ways of thinking about the world, he gave the world a new way of thinking about Alabama.

It may seem odd that the modern concept of biodiversity was born in a place that has often been notorious for disregarding its own diversity.

But perhaps that’s why Ed, more than any writer of the last century, explored how people could and should interact with diversity. I think he believed Alabama could become a model of that relationship, because he understood the profound effects that state’s exceptional natural riches had on him as he was growing up. Concepts like biophilia were his way of articulating the impulses that drove him as a boy to feel the muscular resistance of snakes in his hands, to arrange the wings of butterflies, to study how the minute habits of ants could rock an entire forest.

I think he felt that understanding the biodiversity of Alabama could shape the future of the state, even as it had shaped his future, and as it would shape the world.

If people see Alabama differently in this century, it won’t be because of Mercedes or Toyota or Airbus or those other things we import into Alabama. It will be the result of Ed’s effort to get the world to finally see Alabama for what it is, a great cauldron of life, a global center of biodiversity.

As Ed often ruminated, he had to go up north to find work – at Harvard University where he spent much of his life. But he was always ambivalent about leaving the state that taught him so much. And in the latter half of his life he came back at every opportunity. That’s how I got to know him.

He had access to every great natural area in the world, but he brought teams of scientists to study the insect life of the Red Hills in the center of oak and magnolia diversity in Monroe County and to survey one of the global centers of carnivorous plant diversity in Splinter Hill Bog in north Baldwin County. He declared that the Paint Rock Valley in northeast Alabama should become a world center of research into how forests and ecosystems work. It was as if this rediscovery of Alabama could help explain and confirm the bent of his life.

And for his 88th birthday, he decided he wanted nothing in the world more than a chance to prospect for ants in the Mobile-Tensaw Delta. He swatted his net through the reeds with surprising force, chuckling as he gathered ants that seemed to appear out of nowhere, filing them in vials for identification.

It might have seemed like some serious scientific endeavor, as I pontificated about plants and Ed theorized why we might find ants here, and not over there. Perhaps it was. But on that day we were just two happy boys tromping through the swamp, discovering Alabama diversity as if for the first time.”