This article was originally published in World Wildlife Magazine, Winter 2018

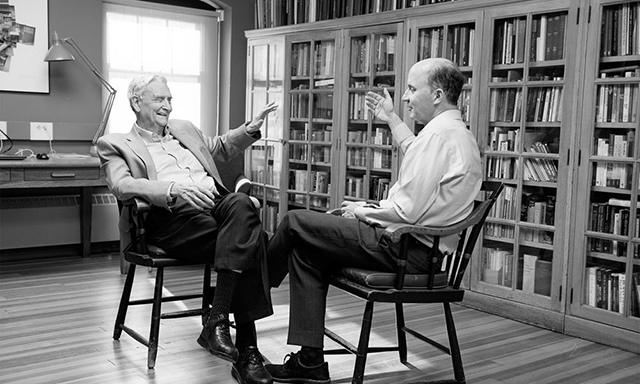

In January 2018, WWF president and CEO Carter Roberts sat down with DR. E.O. WILSON, Pulitzer Prize-winning author, Harvard University Entomology Faculty Emeritus, and the world’s leading expert on ants. Dr. Wilson also served on WWF’s Board of Directors and National Council. They talked about his Southern boyhood, his love of writing, and what he’s going to do when he turns 90 next year.

CARTER ROBERTS: Ed, hello. It’s great to see you again. Thanks for having us.

E.O. WILSON: Hello, Carter. I’m glad you’re here.

CR: When we first met, I was 29 and had just become state director of The Nature Conservancy here [in Massachusetts]. And you were very kind to me. You helped a young kid new to this movement, and I’m grateful. It reminds me that you have two of my most favorite qualities that are rare in combination—intelligence and kindness. And my experience is you’ve always made me feel smarter than I am.

EOW: Well, I’m a truth teller.

CR: Too many times one meets experts and they are so eager for you to be impressed by how smart they are that you just end up feeling unintelligent in comparison. But you, Ed, have a way of making everyone around you feel smart, and it motivates people to do more.

“Climate change is going to be stalled. We will slow, stop, and reverse climate change. Then or now, we must realize that an equal threat to our existence is the accelerating destruction of species and places.”—E.O. Wilson

EOW: I guess it was the way I was brought up.

CR: We’re both from the South. You’re from Alabama—

EOW: Where are you from? I didn’t know you were Southern. I should’ve guessed.

CR: I’m from Georgia. In your case, how is it that a boy from Mobile ended up at Harvard?

EOW: I never thought I’d leave the South. I was at the University of Tennessee beginning my doctoral studies, and one of the professors there wrote a friend at Harvard and said: this kid does not belong here—invite him to Harvard. And he did.

CR: Do you think you have a greater regard for the natural world because you grew up in the South?

EOW: Could be. I think it has a lot to do with being able to be outdoors almost year-round. I was an only child. And we moved around a lot, so I didn’t make large numbers of friends every year. I’d just go into the woods and look for snakes and bugs and butterflies. So that’s how I got started. I always loved the outdoors, but I think it was intensified by growing up in the South. I also had the Boy Scouts, so that helped, when we moved. I attended 14 schools.

CR: You’re an Eagle Scout?

EOW: Oh, yes. I collected almost every merit badge, except for canoeing. I couldn’t find a canoe.

CR: You know now they have a biodiversity merit badge. And WWF is launching a global collaborative with scouting to raise awareness about the loss of nature and what that means for humanity.

EOW: I’m really glad to hear that.

CR: I want to talk to you about your writing career. I think at last count, you’re up to 33 books—is that right?

EOW: Yes, 33. I’m working on books 34 and 35 now, writing them at the same time.

CR: [Speechless].

EOW: By the time they’re both done, I will be 90. And I’ve decided that if my health holds up, I’m going to stop writing books and go back into the woods.

CR: Anywhere specific?

EOW: I’ll tell you what my plans are. I’m going to go down to the Florida Panhandle, to the Torreya State Park, along the Apalachicola River … primarily to just sit there. And then I’ll go up to the Southern Appalachians to do the same … just sit.

CR: It’s a funny thing. When you work on saving nature or you write about nature—it often takes you away from nature. It’s so important for us all to do what we did when we were younger, and that’s to just sit … to just be there.

EOW: To just sit and contemplate nature seems like a luxury, but we could all use a bit more of it in our lives.

CR: Speaking of your writing, I have two questions: First, what’s your secret to writing so prolifically and so well? And second, what advice would you give to someone who wanted to write a book?

EOW: Well, a few things. When I’m working, I like to be alone if I can—in places like the Amazon and Papua New Guinea and when I’m collecting ants and so on. And I’m talking to myself constantly. When I get into an idea that’s formulating, especially when I’m in the field, then I start talking to myself about it as if I was explaining it to someone else. I thought I was unusual in that respect. And then I discovered a paper recently that said 60% of people talk to themselves.

CR: [Laughter]

EOW: And I do it just like having a partner—an alter ego, you know, a cautionary voice that says: ‘Oh, that trail’s too steep for you to try’; or, ‘I’m not sure that makes any sense. What do you mean?’

CR: So, in those conversations is—the book?

EOW: Exactly, in those conversations. And I would then talk about ideas, and develop ideas, explaining them to my alter ego.

CR: When you put pen to paper, though, or when you start tapping on the keys, and you take the conversation and translate it into the written word, you must have enormous discipline to do that.

EOW: I do.

CR: Most people don’t.

EOW: No, but I do. I can work all day.

CR: My college roommate is a writer, and he says that when most people say they want to write a book, what they really mean is they want to have written a book. [Laughter] Because they don’t realize that the work of writing—like conservation—takes tremendous discipline.

EOW: Well, I’ve gotten to where I love it. I love writing. Because what it does, as I was explaining, is to take ideas that are half-formed and allow you to develop them fully and then share them with an audience of people you know share the same passions that you have and want to learn more.

TEXAS LEAFCUTTER ANT (Atta texana) Dr. E.O. Wilson’s contribution to the science of myrmecology—the study of ants—has been extraordinary. A preeminent biologist and a two-time Pulitzer Prize winner, he has written several iconic books about ants, including The Leafcutter Ants: Civilization by Instinct.

CR: To me that’s why your books resonate. It’s not about you. It’s about the audience. And the audience is the hero. You reach them and encourage them to do those great things that are within them. I’d love to get your thoughts on how we can do a better job of cultivating the valuing of nature on the world stage. If I go out and ask the average person on the street to name the biggest environmental issue of the day, they’ll say climate change.

EOW: Of course they will.

CR: They’re not wrong that it’s one of the big ones.

EOW: But climate change is going to be stalled. We will slow, stop, and reverse climate change. Then or now, we must realize that an equal threat to our existence is the accelerating destruction of species and places. Now, we want this to be on the public mind peacefully, but—

CR: Once we lose them, they’re gone.

EOW: They’re gone. So, we must do both.

CR: What conservation strategy resonates with you? If you had to pick one way to address all the challenges we’re up against, what would it be?

EOW: To preserve as much nature as possible.

CR: Your half-earth principle—that we should set aside 50% of the planet as a sort of permanent nature preserve.

EOW: Right. Of course, it will take a lot of work—a lot of accommodations, addressing concerns over property rights and so on. But those are things that can be worked out. And if you can make it a world movement, like avoiding nuclear war or ending poverty, things that everyone agrees with—well, that’s what we need to do. And now I come to the how of it all: We take this immense energy that’s building up in young people and channel it toward the management of biodiversity.