In a new series, “Vanishing: The Sixth Mass Extinction,” CNN’s David Mackenzie and Jon Sutter take an in-depth look at the causes of and solutions to the extinction crisis.

“We’re entering the Earth’s sixth era of extinction — and it’s the first time humans are to blame. CNN introduces you to the key species and people who are trying to prevent them from vanishing.”

Using compelling stories from the field, Mackenzie and Sutter introduce the major problems causing species decline, including climate change, habitat loss, and poaching. Anthony Barnosky, an extinction expert from Stanford, notes that we have about 20 years to change our relationship with nature before we can’t turn back.

What is the solution? CNN highlights E.O. Wilson’s Half-Earth solution to the extinction crisis, noting that if we save have the surface of the planet — half the land and the seas — we can protect 85% of species. Currently only 15% of the land and 4% of the oceans are protected. “Our actions now — or inaction — will matter for thousands of years,” says Sutter. By achieving the goal of Half-Earth — by saving half the Earth for the rest of life — we can stop the sixth mass extinction. Learn more about the Sixth Mass Extinction here: http://www.cnn.com/specials/world/vanishing-earths-mass-extinction

From CNN’s “Vanishing: The Sixth Mass Extinction”

“How to Stop the Sixth Mass Extinction”

By John D. Sutter, CNN

Scientists warn the Earth is entering the sixth mass extinction. Three quarters of all species could vanish.

Editor’s Note: John D. Sutter is a columnist for CNN Opinion who focuses on climate change and social justice. Follow him on Snapchat, Facebook and email. This story is part of a CNN series called “Vanishing.” Learn more about the sixth extinction and get involved.

(CNN) — The Earth is on the verge of a mass extinction event.

To understand how big of a deal that is you don’t have to look much further than the definition of “mass extinction.” It means that three-quarters of all species vanish — forever.

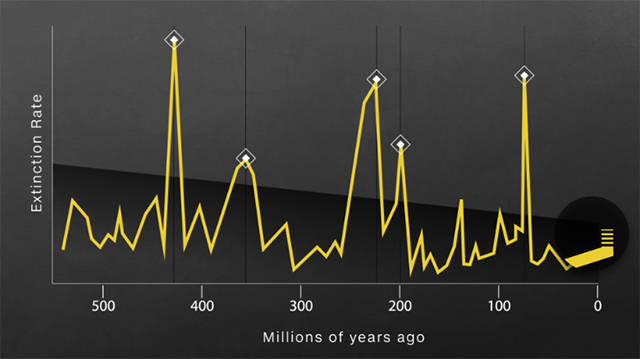

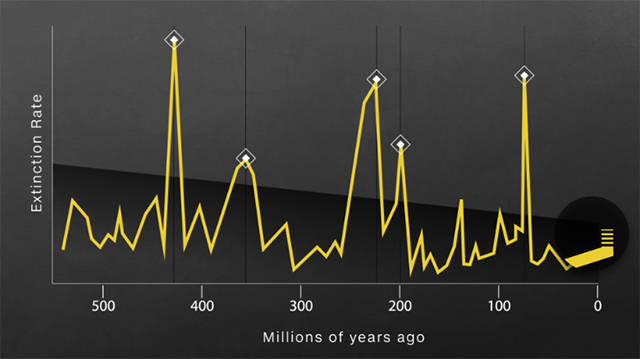

In all of history, that’s happened only five times.

The sixth extinction would be the first caused by humans.

“We are basically annihilating the life on our planet — and that is the only known life … in the entire universe,” said Paul Ehrlich, Bing professor of population studies at Stanford University.

“It’s life that shaped the planet, that made it possible for us to live here. It’s life that still makes it possible for us to live here. (If) we don’t have the diversity of other organisms, we’re done.”

I’ve been reporting on the coming extinction crisis this year for a CNN series called “Vanishing.” And I can tell you that while this topic is enormously depressing, there is some good news: We know how to slow or hopefully stop the sixth extinction.

Anthony Barnosky, another extinction expert, also from Stanford, told me humans have at most 20 years to make sweeping changes about our relationship with nature. If we do that, he said, we can avoid the sixth extinction.

But here’s what needs to happen, according to the experts.

1. STOP BURNING FOSSIL FUELS

Burning fossil fuels and chopping down rainforests is heating up the atmosphere. That’s creating trouble for all corners of the natural world, from the Rocky Mountains, where the tiny pika is overheating, to the oceans, where coral reefs are being decimated as the oceans warm and become more acidic.

We know that to avert the worst of climate change we need to limit warming to at most 2 degrees Celsius. To do that, the world needs to be off fossil fuels this century — hopefully closer to 2030 than 2100. That’s a tall order, but Stanford University researchers have shown we can do it with existing technology like wind, solar and nuclear.

Policies that promote cleaner energy include carbon taxes, cap-and-trade pollution pricing systems and renewable energy tax credits. The Paris Agreement on climate change, ratified by the United States and 115 other countries, also creates a framework for a rapid shift away from fossil fuels. The Trump administration in the United States, however, threatens to move the world’s second-biggest climate polluter away from that agreement and back towards dirty, climate-warming fuels.

2. PROTECT HALF THE EARTH’S LAND — AND OCEANS

This idea comes from renowned biologist E.O. Wilson: Put aside half the surface of the Earth — both land and oceans — for the betterment of the nature and biodiversity. Maybe that sounds like a lot, but Wilson argues it’s necessary if we want to avert crisis. Some 84% of species could be saved if we protected all that land. “That amount, as I and others have shown, can be put together from large and small fragments around the world to remain relatively natural, without removing people living there or changing property rights,” Wilson wrote in an op-ed in The New York Times.

The trouble: We’re not protecting nearly enough, according to experts. Currently, only 15% of land and 4% of the world’s oceans are protected from encroachment by humans, mostly in the form of farms. Already, people have used up nearly 40% of the world’s land for farms and raising livestock — much of it to grow feed for cattle. Eating less meat — or going vegetarian — uses less land (and is far better for the climate; beef is an especially big polluter).

3. FIGHT ILLEGAL WILDLIFE TRAFFICKING

Some of the world’s most iconic species — particularly the elephant and rhino — are threatened with extinction simply because people are slaughtering these majestic creatures to sell their body parts on the black market. Elephant ivory is carved into trinkets. And rhino horn is mistakenly sold as an aphrodisiac.

And there are other less-known markets, too, including those for pangolin meat (a delicacy), giraffe tails (bracelets) and tiger bone (medicine). Efforts to shut down these markets have been grossly inadequate, as the black market in environmental products is estimated to be worth $91 billion to $258 billion per year. Compare that to drug trafficking, the most lucrative black market, which is worth $344 billion per year, according to a United Nations and Interpol estimate.

Experts say better law enforcement is needed to stop poaching. And consumers — especially those in Asia, where wildlife products tend to be popular — need to stop buying these illegal and harmful goods. Groups like WildAid and Education for Nature Vietnam are using advertising campaigns to try to make these products seem uncool.

4. SLOW HUMAN POPULATION GROWTH

It sounds callous, but more people means more food, more land and more resources. Ehrlich, from Stanford, said population growth is one of the main drivers of the Earth’s extinction crisis. The population was about 4 billion in 1980. It’s now 7.4 billion and is rapidly heading for 9.7 billion by 2050, according to the United Nations.

There are ways for each person to conserve, of course. The World Bank says the average American, for example, produces about 10 times as much climate-change pollution per year as an average person from India. And we needlessly use resources we know are harmful. Plastics, for example, are clogging the world’s oceans. We dump the equivalent of one garbage truck of plastic into the ocean each minute, according to the World Economic Forum. Some researchers expect there to be more plastic than fish in the ocean, by weight, by the year 2050. That’s almost unthinkable.

5. RECONNECT WITH THE NATURAL WORLD, AND OPEN OUR EYES

If there’s a fact that underlies all this, perhaps it’s this: We’re no longer connected to nature. We don’t understand it and therefore, naively, dangerously, we figure it’s doing just fine or will rebound. Barnosky, the extinction expert from Stanford, said we think of the natural world like a bottomless checking account when we need to see it as a savings account.

We humans also have ridiculously short attention spans. Issues like extinction and climate change play out over decades, centuries and millennia. Our actions now — or inaction — will matter for thousands of years. “You can have catastrophic events that are seen in slow motion, basically, and not register on people very well,” said Ehrlich. We must find a way to reconnect with nature and to see this wave of extinction for the crisis that it is.

Have other ideas or questions? Please e-mail CNN’s John Sutter: john.sutter@cnn.com.